What is the fundamental essence of “Wa1“ (Japanese harmony or spirit)? There are countless theories: “Wa” is harmony, “Wa” is layered expression, and “Wa” is the unification of “Rigorous Form” and “Rich Soul”. Ultimately, “Wa” is not a concept that fits into a simple theory; it is something to be experienced, contemplated, and inwardly savored.

Through covering the Inshō Kigansai (Seal Prayer Festival)2 at Kyoto’s Shimogamo Shrine (Kamo-Mioya Shrine)3, we came into contact with two extremely contrasting traditions that embody the spirit of “Wa”. One is the small, vermilion Hanko seal4 that engraves individual “Trust”; the other is the splendid layered robe, Jūnihitoe5 that embodies the beauty of “Nature”. We hope to convey the “Wa” that we had experienced through these two cultures.

The Smallest Symbol of Trust: Hanko

The Hanko seal, introduced from China, was initially a symbol of authority, used for the Emperor’s seal and official seals. Due to its precious nature, it gradually became sanctified at courts and temples, eventually leading to the establishment of the Inshisha (Seal Shrine)6.

The Inshisha at Shimogamo Shrine boasts a deep and venerable history, drawing wide veneration today. Every year on the last Sunday of September, the Inshō Kigansai is held—a traditional ceremony where seals that have completed their service are carefully interred. Following prayers in the main sanctuary, a burial ceremony is conducted at the Inshisha, marking the sacred resting place for the old seals.

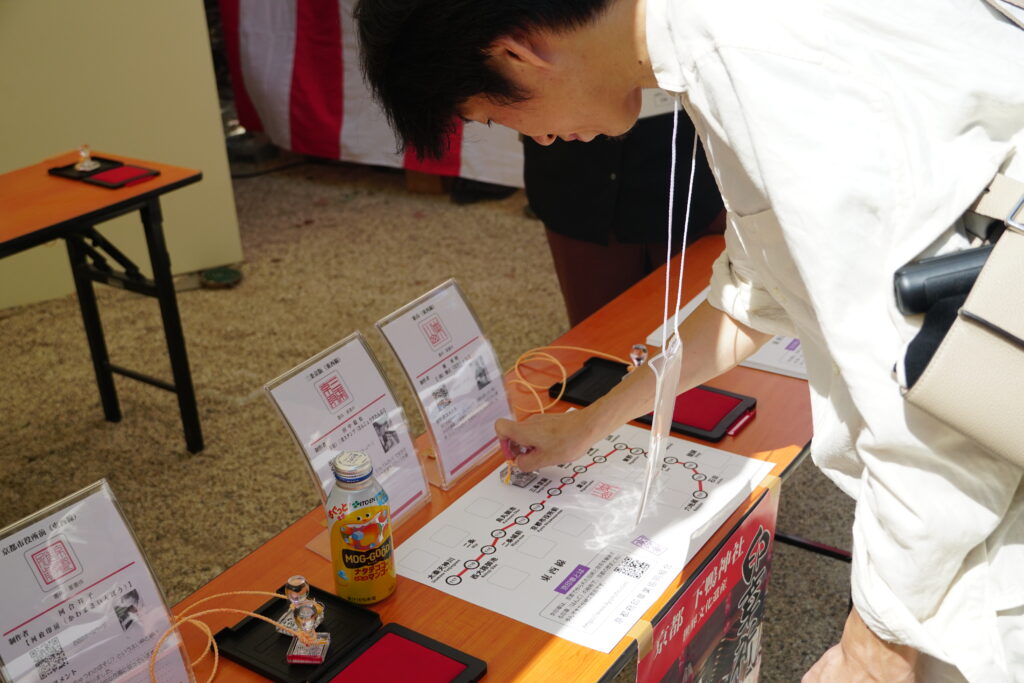

On the day of the festival, a booth for a seal-making experience was set up alongside the reception area outside the shrine. Our discussion with Mr. Kawai, the representative of Kawamasa Inbō7, deepened our understanding of the seal’s essence and its future.

“Rigorous Form”: An unshakable prove of trust

Unlike a signature, the essence of a Hanko is that “it never changes, even if stamped a hundred times”. Because registering it with public institutions grants it strong certifiable power, its creation demands a commitment to “durable materials” and “artisans who can design a unique style every time, even with the same characters”. Kyoto’s seal workshops pride themselves on their deep history and design artistry, establishing the regional brand, “Kyo-Inshō (Kyoto Seals)”8.

The Hanko is traditionally crafted from precious materials such as wood, jade, and metal, and often features carvings on the top. Though small in size, the mass, weight, and meticulous design of the Hanko express the absolute certainty that responsibility is unshakable once the seal is pressed, and the courtesy required in the public sphere. This is precisely the “Rigorous Form”— Weightiness that the Hanko represents.

“Rich Soul”: A carrier and witness of sincerity and history

While the use of seals is declining due to the emergence of new technologies like digital signatures, Mr. Kawai commented that the Hanko will never completely disappear. This is because, in addition to its technical merits, the Hanko is imbued with the owner’s sentiment and the artistic value contributed by the artisans.

For example, real estate transactions in Japan require a registered Jitsuin (officially registered seal)9. Since property is not merely a commodity but a Family Treasure marked by countless memories of the owner, the transaction becomes a poignant handover rich in human feeling rather than a cold exchange. Therefore, using a seal that represents the party’s individuality, and even their family lineage, as proof—instead of a simple encrypted number—is an act that embodies the sincere determination and courtesy of the message: “I have duly accepted this, and I will treat it with care”.

Every time the seal is pressed is an act of engraving the soul and proof onto that spot. Just like a tree grows by increasing its layers, the documents certified by the Hanko in the past and those to be certified in the future accumulate, recording a history of the possessor with the sentiment in that fleeting moment. The seal also serves as a “mirror to the heart” of its owner, becoming a witness to their “Rich Soul.”

Does a soul reside in the Hanko seal? The physical weight of the seal, the weight of responsibility it represents, and the past and future it weaves together with every impression… While attending the traditional ceremony where old seals are carefully consecrated, we contemplated the spirit of “Wa” contained within the Hanko culture.

Weaving “Beauty” and “Soul” into Splendid Robes: Jūnihitoe

The other tradition that embodies “The Weight of Courtesy” is the Jūnihitoe.

On the day of the Seal Prayer Festival, a Jūnihitoe dressing demonstration was held on the Shimogamo Shrine stage. The Jūnihitoe refers to the ceremonial court attire for noblewomen, the Karaginu mo10, established in the late Heian period. It was an adaptation of Chinese clothing, modified to suit the unique Japanese lifestyle of sitting on floors. Following the cessation of the missions to Tang China11, Japan’s fashion culture blossomed in its own style, and the Jūnihitoe was one of the representative in that era.

“Rigorous Form”: A presentation of class society and manner

The “Jūni” (twelve) in Jūnihitoe does not denote the exact number of layers, but simply means “many” or “numerous.” The robe can weigh up to 20 kilograms. Beyond just the physical “weight,” the Jūnihitoe also had strict limitations on its layers that differed according to the wearer’s social rank. Furthermore, the use of colors and patterns changed meticulously by the season. This system truly embodies the “weight of formality and courtesy” required as the formal attire for court ladies. Here, too, we once again experienced the “Rigorous Form.”

“Rich Soul”: A carrier and witness of sincerity and history

While two court ladies assisted with the dressing from the front and back, the Princess (Hime12) was nearly immobile, only slightly extending her hands when the sleeves were put on. Was she perhaps contemplating the ceremony she was about to attend or the events unfolding at the court? The “Kasane” (layered robes, pronounced the same as “Kasa-ne,” meaning layers)13, each with a name corresponding to a season, piled up, and the shifting colors gave the impression of a change in the Princess’s emotional state. When clothing reflects a person’s inner feelings, and a person’s mood, in turn, is changed by the clothes they wear—is this not the expression of the “Rich Soul”?

We must acknowledge that the fashion and attire throughout history reflect not only the era’s lifestyle but also the wearer’s social class and emotional expression. In this context, the Jūnihitoe perfectly demonstrates the confluence of the Rigorous Form and the Rich Soul within Japanese culture.

Conclusion: “Weight of courtesy” in Form and “Pileup of thoughts” in Soul.

Tracing the history of Japan’s traditional culture and analyzing the spirit of “Wa” from the perspective of “Rigorous Form” and “Rich Soul,” fascinating insights emerge.

The Hanko and the Jūnihitoe share a common thread, which can be expressed in a single character, “重”14. The character stands for weight, layers and impression of one thing to another.

“重” can be…

In Hanko seal

- the mass of a jade Hanko

- the pileup of documents and history

- the impression of a Hanko to a document

- the rigor of the law

- the pileup thoughts behind a contract

In Jūnihitoe

- the weight of Jūnihitoe

- the courtesy and manner of Jūnihitoe

- the layering of Jūnihitoe

- the piled up emotion of the Princess

- the shifting between seasons

Both traditions reveal that “Wa” is the spiritual equation where physical weight equals moral authority, and simple layers equal profound meaning. To some extent, we can say “Wa”take the “Rigorous Form” and embed within them the “Rich Soul”, making a harmony of form and soul.

We encourage you to seek out opportunities to experience Japan’s traditional culture and feel the “Soul” hidden within its “Form”!

- 和, Culture of Japan ↩︎

- 印章祈願祭 ↩︎

- 下鴨神社, or 賀茂御祖神社(Kamo-Mioya Shrine) to be precise. ↩︎

- 印章 or 印鑑, Hanko, Seal ↩︎

- 十二単, a style of formal court dress first worn in the Heian(平安) period by noble women and ladies-in-waiting at the Japanese Imperial Court. ↩︎

- 印璽社 ↩︎

- 河政印房 ↩︎

- 京印章 ↩︎

- 実印 ↩︎

- 唐衣裳 ↩︎

- 遣唐使 ↩︎

- 姫, the Princess. ↩︎

- 襲(かさね) ↩︎

- 重, can be read as Jū, Omoi, Kasane ↩︎